Anthroposophic psychotherapy, anthroposophic medicine, trauma and panic attacks

John Lees

Last update: 26.04.2023

Abstract

This qualitative single case study research describes a case of early life trauma leading to dissociation and panic attacks in adult life. It gives an account of the treatment; how anthroposophic psychotherapy is enhanced by anthroposophic medicine, how their mechanisms of action support each other and how anthroposophic psychotherapy works with clients’ spiritual individuality.

Introduction

In this article I will address how our supersensible bodies are struggling today to connect with our inherited physical body leading to both a gap between our higher members and our inherited body and to widespread levels of dissociation especially in the case of childhood trauma. It is for this reason that Rudolf Steiner stated, in his first medical course, that ‘To talk of mental disease is sheer nonsense. What happens is that the spirit’s power of expression is disturbed by the bodily organism’ (1, p. 176). Expressed differently the spirit and soul of traumatized clients are disturbed by the inability of our body to provide a home for them as we enter the physical world within the first few years of life as a result of trauma.

The connection between trauma and the body has been acknowledged scientifically. For instance, McEwen and Getz (2) refer to the fact that, as the child matures, our organ, endocrine and immune systems, and the vital-vegetative functions should establish a state of allostasis (meaning ‘remaining stable by being variable’). But they also refer to how ‘wear and tear that results from either too much stress or from inefficient management of allostasis, such as not turning off the response when it is no longer needed’ leading to ‘elevated blood pressure and low-grade inflammation’ which ‘can over time contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, strokes and myocardial infarctions’ (ibid, p. 2). They refer to this as allostatic load.

In view of this anthroposophic psychotherapists consider the impact of trauma on the body as well as the soul (3, 4) and will refer clients to anthroposophic doctors wherever possible: we ‘learn to treat mental diseases with physical remedies’ since ‘mental and spiritual treatment’ alone will be ‘ineffective’ (1, p. 177). This of course is not always possible since anthroposophic medicine is not always available and so anthroposophic psychotherapists need to learn to emulate the actions of the medicines.

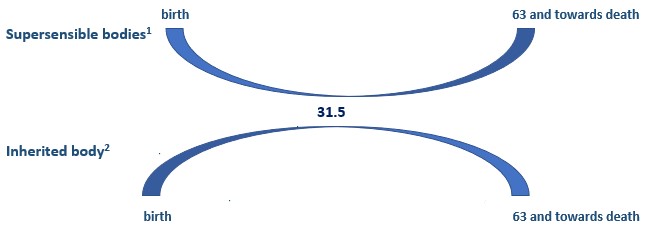

Figure 1 below illustrates the problem of the gap. It shows how the higher supersensible bodies come to earth from the spiritual world, reaching their deepest connection with the earth around the age of 31.5 when the inherited physical body is strongest and how they frequently do not connect.

Fig. 1: The higher supersensible bodies and the inherited body between birth and death

To address this problem I will examine how anthroposophic psychotherapy and anthroposophic medicine work together, how anthroposophic medicine mirrors and intensifies the mechanisms of action of anthroposophic psychotherapy and vice versa and how anthroposophic psychotherapy can emulate the actions of the medicine. I will also demonstrate how anthroposophic psychotherapy works with, recognises and supports the clients’ essential spiritual being – the client’s spiritual individuality or I – to bring about healing.

I will illustrate these principles by examining a case of early life trauma.3 The client spoke of possible sexual abuse around the age of five, although it was just a suspicion with no concrete evidence. The relationship between her parents also broke down at the age of three. However, I came to the view that there was a more fundamental trauma whilst still in the womb brought about by two things. First, a life-threatening situation for her mother during pregnancy because of stage four placenta previn and, second, medical treatment which prescribed steroids for the foetus because it was deemed that her lungs were in danger because of the displaced placenta.

Presenting problem

When the client came to see me in her twenties the main presenting problem was panic attacks. She described a panic attack as being like a ‘weird film’ in which she did not feel as though she was living in reality as her experience flashed from one scene to another. You need to imagine how disorientating it must have been for her as she experienced some situations in life as moving from one scene to another with changes in lighting and music and different camera angles and moods.

One month before coming to see me she experienced a panic attack whilst walking from her mother’s house to her father’s house. The walk lasted for 80 minutes and rather than calming down as she walked she became progressively more panicky so that after she arrived she sobbed and cried for 4 hours.

Over a period of two sessions I asked the client to describe the experience in some detail. The incident took place at about 5pm in evening in January. It was cold and dark; the streets were quite busy. She walked through the back streets. Overall it was a familiar route but she also walked down a road which she did not always go down. She was carrying a bag and after about 20 minutes felt as though her head was ‘expanding; that anything was possible’. She then felt dizzy, started crying and could not see. She tried to walk as ‘fast as possible’ because she was feeling ‘not quite right’, as though she was going ‘down a hole’. She described her thoughts as going crazy. She was trying to calm herself and felt seasick. She felt that she was outside her body with ‘nothing tangible to hold on to’.

Psychotherapy interventions

Introduction

My client’s description of the panic attack highlights her senses4 (5). Rudolf Steiner explicitly relates our human senses to a healthy functioning of the self or the I. We engage in life through sensory perception which enables us to become present in the world and thereby conduct our lives in a self-directed way. If our senses are healthy our I can manage our physical body (6, 7): see also the work of van der Kolk (8). I will return to this important issue later.

Since the trauma was clearly embedded in the client’s body, I referred her to an anthroposophic doctor. She was treated with several medicines.5 But I will concentrate on just one; namely kalium aceticum comp which I view as a quintessentially grounding medicine.6 It addressed the dissociation brought about by trauma. As such it supported and intensified the anthroposophic psychotherapy interventions. It strengthened the client’s connection with the earth and helped her to establish the roots of her incarnation.

I will now look at how anthroposophic psychotherapy and anthroposophic medicine worked together and how anthroposophic psychotherapy strengthened this collaboration by recognizing, working with and supporting the activity of Andrea’s I (spiritual individuality or self).

Complementary treatment

My basic anthroposophic psychotherapy intervention emphasised grounding techniques which involved asking the client to describe situations in some detail (9, p. 56). The description of the panic attack when walking from mother to father’s house was an example of this. But there were many more examples. The aim was to enhance her feeling of identity (ibid, p. 27) based on the principle that the core of our being, our individuality or I, ‘experiences’ and ‘defines itself through the sensory impressions’ (ibid, p. 28). Additionally as in auto-immune diseases Andrea’s trauma prompted a dislocation between her I and its organic embodiment and this in turn disrupted her soul life. This anthroposophic psychotherapy intervention was supported by the kali aceticum comp which strengthened her connection with the kingdoms of nature. It prompted reconnection with the substance forming metabolism in the human vegetative system, which then provided resilience both in her body and, as a result of this, her soul and spirit.

Anthroposophic psychotherapy addressed the problem in her soul life and the kali aceticum comp addressed the problem in her body. Both interventions helped her to connect to the surrounding world.

Working with the client’s spiritual individuality

I took the view that my client’s description of her panic attacks provided an accurate phenomenological observation of her problems and provided a framework for understanding and giving meaning to the problems and thereby in terms of salutogenic principles (10) her I gave me the capacity to manage the problems. This had four aspects.

First, she gave a clear picture of the impact of the panic attacks on her senses (5, 11).4 We connect with the world around with the so-called middle senses of smell, taste, vision and warmth. In her description of the panic attacks she spoke about the cold and dark, the busy streets were busy and described the route which she took. Additionally she was crying, could not see and felt she was going into a hole. But these perceptions were overwhelmed by her perception of what anthroposophy refers to as the bodily senses – the senses of equilibrium, movement, life and touch. In the walk she lost equilibrium and felt dizzy, her movement made the situation worse rather than better leading to sea sickness, her life force was drained by the end of the walk and she collapsed in tears for four hours and, as regards the sense of touch she felt that she had nothing to hold on to. Her sense of her own body overwhelmed her connection with the world. Her consciousness was dominated by her bodily state thereby losing her connection with the world around and the social environment. So subsequent interventions aimed at re-establishing the connection by emphasizing the ‘middle’ senses.

Second, her descriptions gave an insightful account of anthroposophical developmental psychology or biography. Ideally in our twenties7 we begin to live ‘in the periphery, absorbing the world in perception and approaching it in desire’ and as a result of this develop a personalized way of relating to the world (3, p. 257). However, as already discussed, her capacity to do this was limited. She became cut off from the world around whenever she experienced a panic attack because her consciousness was focused on her bodily senses. Consequently she struggled to achieve the developmental ideal of this age which is expressed as follows: ‘how do I experience the world and myself through it’ (ibid, p. 257). Put differently she had difficulty in establishing ‘firm ground’ under her ‘feet’ (12, p. 63). Her experience of living independently in the world was limited by the fact that she was living in her mother’s house with her step siblings and had no intimate adult relationships independent of her family, even though she was an intelligent, capable, sociable and extremely pleasant to be with. Logically there was no reason for this. Her consciousness of the temporal dimension of her life – or biography – was compromised. She struggled to move forward into the future. The need to move on in her life then became a central focus of the psychotherapy which provided containment for her as she took challenging and frightening steps into the future.

Third, her descriptions of the panic attacks demonstrated her difficulties in maintaining a consistent perception of the world over short periods of time; instead she moved from one scene to another as in the movie analogy. I took the view that this was a microcosm of the general state of her life as she had not built her independent life. Although the panic attacks were relatively short, they were phenomenological indicators of her general insecurity in building her independent life in the world after the age of 21 with a clear identity. As the work progressed, she produced and demonstrated many similar inconsistencies as she described the situations and events of her day-to-day life. So an important part of the psychotherapy was to help her to create and maintain a coherent and clear biographical or developmental perspective on her unfolding life.

Fourth, and bringing these points together, her phenomenological observations created the circumstances where I could help her I to become active and give her life direction, meaning and purpose. Indeed I always note the client’s insights even when the client is unaware of them and use them in my therapeutic interventions. So despite the difficulties I took note of the way in which her spiritual individuality was giving both her and me insight into her lived circumstances. She was in effect providing a clinical assessment of the problem and, as such, her descriptions were more useful therapeutically than any diagnostic manual.

I took the view that such insight was possible because her I (or spiritual individuality), even though struggling to take command of her life, was present although not fully connecting with her other supersensible members, her physical body and the world. So this enabled her to make fascinating and wise comments about her psychological state. She had a creative perception of her inner life but her perception of the outer physical world was limited. So my overall therapeutic aim was to recognise the wisdom of her spiritual individuality, provide a containing space in which it could flourish and help her to ground it in the physical sense world and the social environment. Her perceptions in the panic attacks were not supported by a continuous state of interest in the world and she could not fully integrate her perceptions and her inner desires and impulses with the social environment and so I aimed to help her to do this.

The key intervention in helping her I take command of her life was to give her a coherent view of what was happening in her life based on the principle of salutogenesis (10), already referred to. This had three elements: to understand what she faced in the world, see its meaning and, as a result of this, manage it. The technique has been referred to as ‘substitute self-coherence’. The therapist aims to remember the content of previous consultations, develop a ‘unified image of the client’, provide a hypothesis of the problem, test the hypothesis and give a solution to the problem (9, p. 375). It resembles the principles of the pedagogical law (6).

An example of this technique occurred when I was preparing this article. I reminded her of what we had discussed in previous sessions regarding panic attacks. Having discussed the panic attacks she then spoke for the first time about an eating problem. I asked her for an example and she spoke about having some food in her cupboard – several Japanese sweets – which she had bought for her sister’s birthday. She described how she ate all of them and, in response to my enquiries, what was going on inside her when this happened – belly tight, nausea, dissociating, becoming robotic, nothing else existing, feeling sick and then ‘throwing up’ in the shower, the toilet or in her room depending on who was in the house. She went on to describe the experience as a ‘control thing’. In effect she blamed herself for the problem, not for the first time. This gave me the opportunity to challenge this and say that it was not so much a problem arising out of trying to control the situation but that the panic attacks and the eating problems came about because her insightful I was not strong enough to manage these situations and so was not able to steer her life. This intervention fulfilled all the substitute self-coherence principles simultaneously. I linked the session to previous sessions, referred to herself (a ‘unified image’ of her I or spiritual individuality), provided the hypothesis that her problems were occurring because the her spiritual individuality was unable to take command of her life and tested this hypothesis to bring about a solution to the problem – a process which pervaded the rest of the work. In this session she immediately responded to my comment about herself by saying that she recognised that she had ‘issues with her relationship with herself’. We were in complete accord on this point.

The work is still ongoing and is driven by such anthroposophic psychotherapy interventions as those described in this article.

Conclusion

The case has provided a clear example of how ‘the spirit’s power of expression is disturbed by the bodily organism’ – particularly the senses. It has also addressed the basic principle underpinning any anthroposophical treatment; namely, the centrality of stimulating the healing power of the client’s individuality or spiritual I. As regards the anthroposophic psychotherapy treatment I need to emphasise that this article emphasizes my idiosyncratic way of doing anthroposophic psychotherapy. I do not intend the principles and techniques I have described in this article to be generalized or protocolized. The article is an attempt to encourage the reader to find their own style.

Notes

1 Etheric body, astral body, and I or spiritual individuality.

2 Physical body.

3 The client has given written consent to use the material for the purposes of teaching, research and publication. This included the stipulation that that ‘in the case of publication it is possible that someone somewhere may recognise me’.

4 Rudolf Steiner speaks of four bodily senses (touch, life, movement, balance) which give us an awareness of our inner state, four senses which give us an awareness of the world around (smell, taste, vision, warmth) and four higher spiritual senses (hearing, language, thought, ego) which enable us to see beyond appearances in the world around.

5 Belladonna, ferrum siderium, aurum, argentum bryophyllum, conchae, cuprum, hepar magnesium and kali aceticum.

6 Kali aceticum comp revives an alchemical process from the early seventeenth century which has been renewed in anthroposophic medicine. The medicine has four elements in homeopathic potencies: wine made of course out of grapes, stibium from the mineral antimonite, saffron from the crocus stivus plant, polyps from red coral. The wine-making process provides the basis of the medicine. The grapes are harvested, crushed and fermented. The preparation of the medicines then involves the alchemical principle of producing salt at the bottom of the wine barrel, bringing about a sulphur process because of the heat of the fermentation and concluding with the mercury vinegar process. This is then combined with the mineral world (stibium), the plant world (saffron) and the animal world (polyps). The medicine thereby connects us to all the kingdoms of nature and thus with the earth to address dissociation [13]. In a notebook entry of 1921 Rudolf Steiner said that the remedy addresses, amongst other things, a ‘tendency towards dissociation of psychological content with consequent obsessive-compulsive thoughts and distorted perceptions’ (14, p. 764).

7. The phase of life from 21-28 is called the sentient soul.

Bibliography

- Steiner R. Spiritual Science and Medicine. CW 314. London: Rudolf Steiner Press; 2013.

- McEwen BS, Getz L. Lifetime experiences, the brain and personalized medicine: an integrative perspective. Metabolism – Clinical and Experimental 2012;62(1):20-26. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2012.08.020.[Crossref]

- Treichler R. Psychiatry. In: Husemann F, Wolff O (eds.). The Anthroposophical Approach to Medicine. New York: Anthroposophic Press; 1989, p. 255-379.

- Bott V. Anthroposophical Medicine. London: Rudolf Steiner Press; 1978.

- Steiner R. Anthroposophy. In: Steiner R. A Psychology of Body, Soul and Spirit. CW 115. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press; 1999.

- Steiner R. Curative Education. CW 317. London: Rudolf Steiner Press; 1972.

- Steiner R. Theosophy. CW 9. London: Rudolf Steiner Press; 1970.

- van der Kolk B. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking; 2014.

- Dekkers A. A Psychology of Human Dignity. Great Barrington: Steiner Books; 2015.

- Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International 1996;11(1):11-18.

- Soesman A. Our Twelve Senses. Stroud: Hawthorn Books; 1990.

- Burkhard G. Taking Charge. Edinburgh: Floris Books; 1997.

- van Dam J, van der Steen P, van Oort T. Kali Aceticum comp. In: van Tellingen C (ed.) Vade Mecum. Chestnut Ridge, NY: Mercury Press; 2007.

- Vademecum of Anthroposophic Medicines. 2017, München: Association of Anthroposophic Physicians; 2017.