Anthroposophic modalities in the treatment of dissociation and anxiety in adolescence

An approach to multidisciplinary treatment of dissociation in the context of intergenerational transmission of post-traumatic stress disorder

Henriette Dekkers in cooperation with the doctors of the anthroposophical "Therapeuticum Haarlem" in the Netherlands

Last update: 19.07.2022

Introduction

Unprocessed intergenerational transmission of trauma usually occurs at an unconscious nonverbal level from generation to generation. In the absence of narratives describing parental trauma-induced behaviours (1, 2), the ‘ghosts of the past’ (3) kindle unconscious anxiety and dissociative states in successive generations as well as physiological adaptation to traumatic stress (4). Restoration of the traumatized attachment bond between parent and child is the most effective intervention to facilitate healing and to prevent further intergenerational trauma-transmission (5).

This contribution presents a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for the pathogenesis and treatment of dissociation and anxiety in adolescence in the context of intergenerational transmission of parental Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The general premises on this important topic have been specified in a singular case study as a practical clinical illustration.

The focus of attention in the presented clinical example has been the enduring anxiety provoking parental behaviour towards an adolescent child. The choice of therapy has been a ‘familial systemic approach’ for both parent and the adolescent child. All therapeutic interventions aimed at a break-down of intergenerational transmission of PTSD by restoration of the traumatized attachment bond. Prior to systemic therapy, the parent and the adolescent child had undergone separate trauma-treatment by the same therapist. The multidisciplinary approach included Anthroposophical Medicine related to psychosomatic disorders caused by prolonged exposure to intergenerational transmission of trauma.

Aims and objectives

Prevention of intergenerational transmission of trauma

Assessment of Intergenerational transmission of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and PTSD (6, 7) should be taken into account when previous treatments for anxiety symptoms in a child have failed to improve their presenting problems. This is also the case when a child appears to be the symptom-bearer of intra-familial dysfunctionality, the so-called ‘identified patient’ (8, 9) - indicated as early as 1920 by Rudolf Steiner in his “statement to psychiatry”. Exposure to dysfunctional education and anxiety-provoking parental behaviour in the context of his or her own unresolved trauma, has deleterious effects on both the mental as well as the (psycho-)somatic health of the child (8). The Kaiser study into ACE (10) emphasizes these pathogenic effects upon body, soul, spirit and prospects in life (4).

Implementation of interventions in the here and now of reciprocal parent-child anxieties mounting to dissociation

Extreme anxiety often generates a state of dissociation in order to endure the unbearable. Dissociative states block consciousness in perception, emotion-regulation and deliberate actions. Rooted in existential anxiety, dissociation provokes the survival instincts of the life or etheric body, eliminating soul and ego consciousness. Vehement survival modes occur in states of dissociation, along with a sense of depersonalization or “Selbst-Entfremdung”. Subsequently, they tend to be inaccessible for memorizing and, therefore, inaccessible for therapeutic interventions. Our experience with PTSD symptoms and dissociative states have highlighted the importance of clinical awareness of symbiotic, escalating dissociative states between parent and child in the here and now to create healing interventions in the treatment. Psychotherapeutically it required a “holding” attitude, in which the therapist creates a safe therapeutic relation providing shelter, warmth and trust for both the victim (the child) as well as the perpetrator (the parent, once him/herself a victim). Such a relationship enables the therapist to balance and de-escalate reciprocal trauma re-experiencing and dissociation at the very moment of occurrence in the sessions. Both aspects – the clinical awareness, as well as the “holding” attitude – have to be implemented in restoring the parent-child relationship, enabling mutual powerlessness to be overcome. The case study presented is an attempt to elaborate on these assumptions, extending actual outcomes of research and knowledge on the theme through knowledge based on anthroposophy.

Triple assessment and anamnesis

Psychotherapeutically, unresolved parental adverse and traumatic life experiences require a careful approach to avoid a breakdown of the therapeutic relationship, followed by the risk of drop-out of the parent and /or the child. Consequently, all symptoms and anxiety-coping strategies of the child and the parent, as well as their interactions in emotionally charged situations, were examined in assessment and diagnosis. A precise anamnesis of the parental trauma was required including its roots in intergenerational transmission. Clinical awareness of the mutuality and synchronic escalating, dissociative states in both parent and child was carefully investigated.

General outlines of the process of assessment and therapeutic interventions

1. Intergenerational assessment and the prevention of ‘dropping out’ by the parent

It is of utmost importance to prevent distrust, as well as any suspicion or sense of accusation in the mind and the soul of the parent to prevent drop-out of the parent, and even worse: to enhance the risk for worsening violence at home. For this reason an extensive assessment of the individuals as well as third parties has to be carried out. This has to include not merely the dimensions of the incurred PTSD, but the severity of incurred developmental somatic and psychosomatic effects as well, as can be done in In any multidisciplinary setting, including an anthroposophical Therapeuticum.

2. In the presented case the process entailed the following steps:

- The presenting problems of parent and adolescent child were examined separately. Subsequently their somatic, psychosomatic, and psychological symptoms have been assessed.

- The anxietis of the PTSD of the parent, underlying the explosions of violence, have been thoroughly investigated, including exploration of the course of life in the context of intergenerational trauma transmission.

- Finally, an assessment of the constitutions and characteristics of the individualities was carried out.

Altogether this extensive proved to be effective to bridge, psychotherapeutically, the inimical gap of the “anxiety loaded abyss” between parent and adolescent child, as the both of them appeared to bear symptoms of prolonged exposure to ACE’s (10). These had become manifest in psychological disturbances in thought, memory, emotional and volitional field (1), as well as physiologically in the endocrine and the immune system (4, 11, 12, 13). Both patients appeared to be the symptom-bearers of dysfunctional and traumatized families along the lines of “the row of transmission” which Rudolf Steiner (14) calls the pedagogical law running from ego-dysfunction (the grandfather) to soul-impairment (the parent) to functional disorders (the adolescent child).

3. Therapeutic findings in this case study , the intergenerational trauma transmission

The adolescent appeared to be the fourth generation in succession with intergenerational transmission of PTSD. War experiences during WO II had demolished the great-grandfather, whose unspoken and unresolved experiences of being a prisoner of war broke his spirit and physical health. Instinctively his unresolved PTSD was transmitted to the next generation, the grandfather being demolished in soul and trust in life. This grandfather of the adolescent developed antagonism and hatred against any sign of emotional weakness and dependence. As a result of this, he would emotionally and physically harass his very own child – the parent in this case – from early childhood onwards. The story would have continued to repeat itself, were it not for the shipwreck on all relational, emotional, somatic and functional levels of one of them – the adolescent child.

4. Therapeutic intervention: a general premise to implement psycho-education

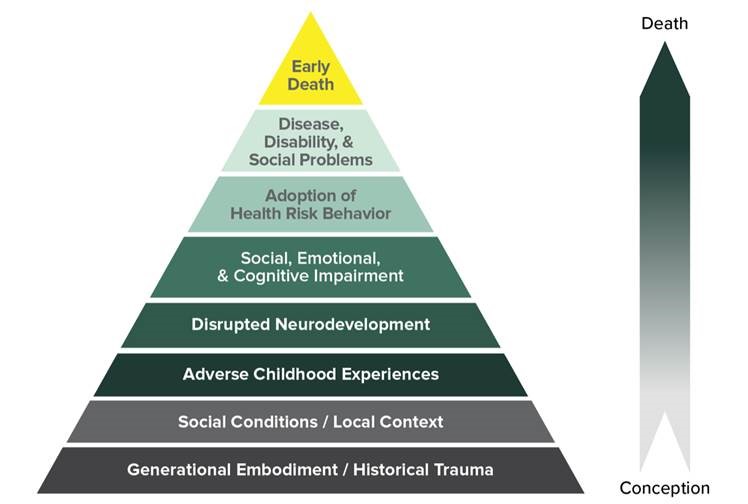

Fig. 1: Mechanism by which adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) influence health and well-being throughout the lifespan. Copyright: www.wavetrust.org

It is common knowledge that parental violence and harassment of children is a difficult area to access for therapeutic systemic interventions, although it is morally, medically and therapeutically clear that stopping therapeutic systemic interventions, although it is morally, medically and therapeutically clear that stopping the maltreatment of, and violence towards the child is a core target. Bearing in mind that maltreatment often takes place in a dissociative state of self-alienation, prior comprehensive psycho-education creates a solid point of psychotherapeutic departure.

5. Providing the narrative of transgenerational transmission in this clinical case

Our approach started with psycho-education on ACEs based on the findings of the Kaiser Study (see (5)). We described, in general terms, to both parent and adolescent child, the detrimental influences which have an impact upon psyche and somatic health of children. By departing from this general view on ACEs and intergenerational transmission of trauma, we could avoid parental defence mechanisms and guilt feelings to arise. Despite the potential limitations of verbal processing in representing and imaging traumatic experiences, having a narrative of life is important for creating a sense of reality and a meaningful and authentic sense of self (15). We would refer to fundamental research in the field of ACEs (4), as well as to Rudolf Steiner´s and Ita Wegman´s writings (8) on the detrimental effects of prolonged activation of the sympathetic nervous system at the cost of the para-sympathetic part of the autonomous nerve-system.

6. Assessment of (psycho-)somatic symptoms and constitution

We conducted two separate intakes, assessments and diagnosis of the parent and the 16 year old adolescent child before entering upon a systemic approach. Hetero-anamnestic information was obtained with informed consent from both patients.

The adolescent child: thin; medium length; pale skin; unbalanced posture. Presenting symptoms:

- somatic symptoms (extreme exhaustion; chronic activated stress-system; weakened immune system manifest in recurrent inflammations, slow recovery of illness like Lyme- and Pfeiffer’s diseases; food intolerance; frequent migraine attacks; light symptoms of scoliosis)

- psychosomatic problems (chronic tensions in chest and in breathing; irritable bowel syndrome; allergic reactions; low body temperature; excessive need of sleep)

- psychological problems (anxiety and high level of self-defence; hyper alertness; frequent episodes of dissociation; exhaustion; school dropout; mood disorders oscillating between panic, rage and depression; nightmares; auto mutilation; increased startle reactivity

The parent: strong, tall, muscular, ‘wear and tear’-tired. Presenting symptoms:

- somatic symptoms (exhaustion, tachycardia, weakened immune system manifest in recurrent incidences of flu, slow recovery)

- psychosomatic symptoms (sleep disorders, continuing agitated sensations of stress, low back pains)

- psychological problems (hyper-alertness covered by social compliance; anxieties to fail; excessive need to be in control; high levels of self-defence; disruptive moods of aggression, disconnection of memories, emotional disconnection, harassment of his children, restlessness, irritability, ruminating and compulsive thoughts, workaholic)

7. Explaining the laws of intergenerational transmission of PTSD to enhance consciousness and resilience

It is of importance to explain your therapeutic approach and goals, in this case by describing to what extent both parent and adolescent child were powerless, captured in their survival modes and mutual suffering. We could explain:

That a parent in a dissociative state tends to repeat his own incurred childhood traumatization (2).

- That parental understanding of the detrimental effects of his or her upbringing would be a prerequisite.

- That the need to stop the mutual entanglement was urgent in the light of aggravating detrimental health conditions of the adolescent child, psychologically, somatically and psycho-somatic.

- That intergenerational transmission of trauma had to cease by comprehension and transformation of destructive patterns and dissociations, and that new competences had to be acquired.

8. Therapeutic interventions: treatment of choice

The adolescent’s symptoms of profound anxiety, desperation and aggravating developmental breakdown dominated the picture, exacerbated by her parent’s denial and apparent amnesia of any acts of violence. Consequently the treatment priority of choice was the systemic approach to bring to consciousness the reciprocal dissociation, amnesia and re-traumatisation. The prerequisite of gaining trust and providing emotional safeguarding for both patients had already been obtained through the comprehensive anamnesis. Both parent and adolescent child were taken seriously and felt thoroughly understood in their existential fears, attacks and feeling threatened. This appeared to create the bottom-line for a gradual de-freezing and de-dissociation during therapy, specifically when anxieties and distrust would emerge.

9. General departing points on dissociation and therapeutic interventions aiming at entangling interactive dissociations and re-traumatization

Dissociative states profoundly impair perception, attention, and memory. In a dissociative state a patient will become depersonalized, unable able to perceive reality, impaired to feel and to judge, let alone recollect and memorize what he or she has done, what has happened – at home as well as in therapy. From an anthroposophical perspective, in dissociative states, the soul and the ego or anthroposophical: the psycho-physiological embodiment and the “I”-organization will be squeezed out of their ordinary physiological cohesion. They are side-lined in their functioning, whereas an existential but unconscious “vehemence to survive” becomes operative. These kind of survival explosions – or implosions – have to be attributed to the vital or ether body, erupting and overwhelming the human consciousness with “volcanic violence”, inaccessible to reasonable or emotional interventions – be it of therapists, be it of partners or children. As Peter Fonagy admonishes: “Don’t go for the violence of the patient!” Aggression serves as a survival mode amidst a sudden abyss deep collapse of Self” (16). Academic research in the field is growing which highlights these dynamics.

Dissociative states can roughly be divided into different states and behaviours:

- Speechless terror and vagal breakdown: dissociation of physiological survival functions (17).

- Re-traumatization, intrusive memories and bottomless existential anxiety: dissociation of consciousness.

During the sessions the communication between parent and adolescent would frequently escalate and lapse into states of dissociation of the type 1 as well as of the type 2.

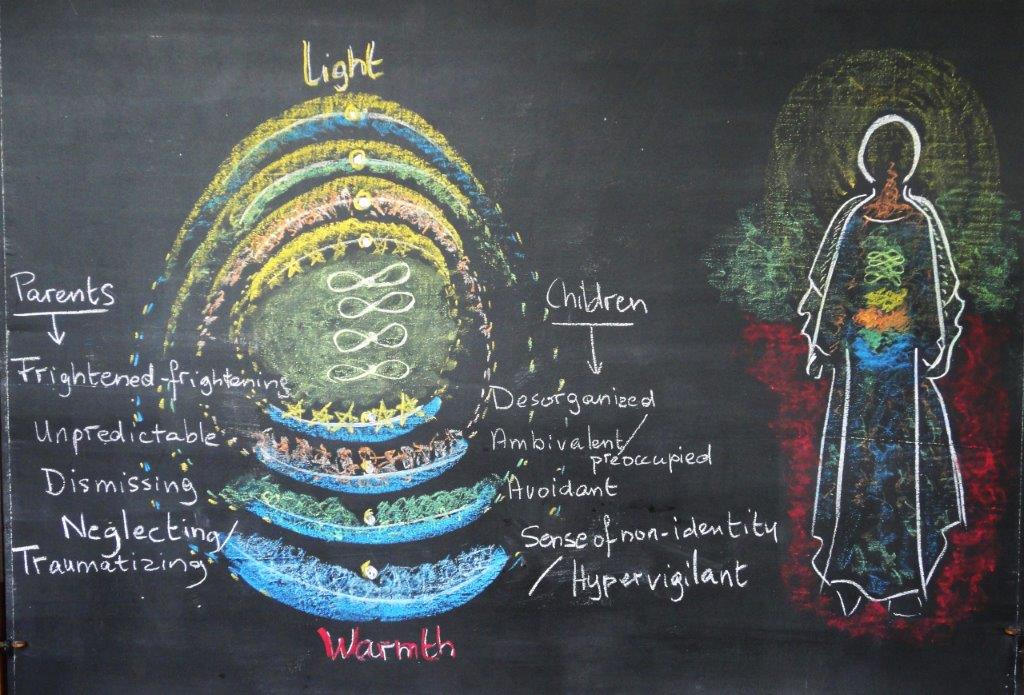

Interventions during treatment to de-dissociate. Awakening the four body-related sensorial systems

During the sessions, being alert and aware of the reciprocal parent-child anxieties mounting to Dissociation and their different physiological phenomena, was a key feature of the therapeutic work. It appeared to be of utmost importance to discriminate between “speechless terror” and “re-traumatization” during the incidents of reciprocal dissociation. Noticing the difference in dissociative interactions into which parent and adolescent lapsed opened new doors to interventions. At some occasions the father would erupt with fury and harassment, re-enacting unconsciously his own traumatization whereas the girl would have an absent gaze of speechless terror.

I would then and there stop the dialogue, give a break and some drinking – which facilitates de-dissociation by re-activation of the fluid circulation (the vitalizing level) and the re-uptake of deeper breathing (the soul level) (18). The therapeutically indispensable attitude of “holding and congruent attuning in comprehensive compassion” to such re-traumatizing states of parent or child, made such interventions possible.

The seven steps to de-dissociate during the sessions would be repeatedly performed and rehearsed by both father and adolescent:

- Awakening consciousness in the here and now: Realizing the state of dissociation and awakening to its actual presence in the room.

- Awakening the physical body in the here and now: Perceiving one’s own physical body by means of activation of the sense of touch.

- Re-vitalizing; calming down the stress: Drinking fluid (tea, water) deepening the breathing, thus activating the sense of life.

- De-freezing and freeing the proper governance in movement : Standing up and walking around, kindling the sense of movement and thus the blood circulation.

- Regaining equilibrium: taking a standing position from one focal point the whole space, re-adjusting to a equilibrium.

- Regaining governance in one’s proper soul: Speaking out loud some simple vocalizations, thus freeing the alienated soul and activating the vocalizing of the soul.

- Readjustment to one-self: Return to the previous point of departure, trying to perceive “I am here”.

After the break both parent and adolescent carefully but phenomenological were set in motion to re-view the dissociative or re-traumatizing process into which they had interactively lapsed. These mutual counter-dissociative interventions appeared to have a healing effect and furthered mutual acknowledgment and understanding.

10. Anthroposophic medications (19)

As both the parent as well as the adolescent child refused regular medicine, it appeared appropriate and effective to give them anthroposophic medication. The father was anointed with Aurum / Lavandula comp. ointment WELEDA to quiet down his anxiety driven explosions; he also received Aurum / Apis regina comp. WALA subcutaneous to support his exhaustion. The adolescent received Kalium Aceticum comp. D6 trit. WELEDA to engage the “I”-organization in the anabolic processes of the metabolic system and stimulate the parasympathetic nerve system; she received Aurum / Stibium / Hyoscyamus globuli WALA to de-dissociate in her anxiety driven paralyzing dissociations; finally she had “Einreibungen” with Aurum / Rosae / Lavandula oil DR. HEBERER as a first gesture to reinstall life-trust through the sense of touch.

11. Psychotherapeutic results: stopping the chain of intergenerational transmission of PTSD

The "proof of the pudding" happened in the home situation. In an outbreak of outragenous temper of violence towards to younger siblings, the adolescent stepped into the agonizing scene and took her fahther in her arms, whispering in his ears as not to make him ashamed in the eyes of the terrorized siblings: "Are you feeling alright, Daddy? Shall I bring you a glass of water?" Then and there, the parent's state of dissociation broke down, and he sobbed in her arms, feeling her true care and love. "How can you love me when I am like this?" he finally could utter. In doing this holding and comforting in this way, she rehearsed what she had experienced again and again in therapy: the holding understanding and compassion with the father as well as with herself by the psychotherapist.

The door had been opened towards stopping the chain of intergenerational transmission of PTSD.

Fig. 2: Pathology of the four body oriented sensorial qualities of touch, life, movement and equilibrium. De-dissociation as a facilitator of embodiment © Henriette Dekkers

Bibliography

- Van der Kolk BA. The complexity of adaption to trauma. In Van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L. Traumatic stress: the effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body and society. New York: Guilford Press; 2006.

- Van der Kolk BA. The body keeps the score: mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. Chap. 4: The anatomy of survival. New York: Viking Penguin; 2015.

- Fraiberg S, Adelson E, Shapiro V. Ghosts in the nursery: a psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant–mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 1975;14(3):387–421. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)61442-4.[Crossref]

- Danese A, McEwen B. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Psychology & Behavior 2012;106(1):29-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019.[Crossref]

- Isobel S et al. Mental Health Research Sydney Australia. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2018;14735.

- Apter T. The insidious legacies of trauma. Website post on May 11, 2020. Available at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/domestic-intelligence/202005/the-insidious-legacies-trauma (04.07.2022).

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annual Review Neuroscience 2001, 24: 1161-1192.

- Steiner R. Zur Psychiatrie. Votum, Dornach, 26. März 1920. In: Physiologisch-Therapeutisches auf Grundlage der Geisteswissenschaft. 3. Aufl. Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag; 1989, S. 262-270.

- Steiner R. Pedagogical Conferences for the Teachers, GA 300 C, 50 / 51, and 133 / 134.

- The landmark Kaiser ACE study from 1995 – 1997 on 17.000 subjects on Adverse Childhood Experiences conducted by the Centres for Social Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the ‘Kaiser Permanente’ into Relations between ACE’s and psychic and physical health in life. See also https://nhttac.acf.hhs.gov/soar/eguide/stop/adverse_childhood_experiences (04.07.2022).

- McEwen BS. Redefining neuroendocrinology: Epigenetics of brain-body communication over the life course. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 2018;49:8-30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2017.11.001.[Crossref]

- Steiner R. Die Erkenntnis des Menschenwesens nach Leib, Seele und Geist. Vortrag vom 2. August 1922. 3. Aufl. Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag 1995. “Once we realize that the brain is shaped under external influences, we can appreciate how important these influences from the outside are. We see that they are tremendously significant once we understand that they affect everything that takes place in the brain.”

- Steiner R, Wegman I. Grundlegendes für eine Erweiterung der Heilkunst nach geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen. Kap. Blut und Nerv. 7. Aufl. Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag; 1991, S. 40-44.

- Steiner R. Allgemeine Menschenkunde als Grundlage der Pädagogik. GA 293. 10. Aufl. Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag; 2019.

- Connolly A. Healing the wounds of our fathers: intergenerational trauma, memory, symbolization and narrative. Journal of Analytical Psychology 2011 Nov;56(5):607-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5922.2011.01936.x.[Crossref]

- Bateman A. Fonagy P. Mentalization-Based Treatment. Psychoanalytic Inquiry 2013;33(6):595-613. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2013.835170.[Crossref]

- In the state of speechless terror “[…] The nervous system shows an opposite phenomenon. In the para-sympathetic nervous system which permeates the organs of digestion, the etheric body is paramount. The nerve organs that are involved here, are primarily life-generating organs. The astral and ego-organizations do not organize them from within but from without. For this reason the influence of the astral and ego-organizations working upon these nerve-organs is powerful (= activating the Sympaticus). Passions and emotions have a deep and lasting effect upon the para-sympathetic nervous system. Sorrow and anxiety will gradually destroy it.”

- Schmall C. Neurologische Korrelate von Dissoziation. Unveröffentlichter Vortrag Berlin 02.07.2010 1st. International Congress on Borderline Personality Disorder.

- Gesellschaft Anthroposophischer Ärzte in Deutschland/GAÄD, Medizinische Sektion am Goetheanum (Hrsg.): Vademecum Anthroposophische Arzneimittel. 4. Aufl. München: GAÄD; 2017.